By the dawn of the 1960s, Ralph J. Gleason was recognized as one of the pioneers of jazz criticism. His first reviews appeared in 1934 within the college newspaper at Columbia University, and a few years later, he launched “Jazz Information”, one of the first jazz periodicals in the United States. The Dixieland revival was just starting when Gleason moved to San Francisco. While Gleason preferred modern music, he successfully produced several concerts with the old masters and the young revivalists. In 1950, he joined the staff of the “San Francisco Chronicle” and soon became the first full-time jazz critic on a major newspaper. Within a few years, Gleason was also a regular contributor to “Down Beat”. He developed long-standing friendships with Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Carmen McRae, and the Modern Jazz Quartet, and championed their work through his liner notes, newspaper reviews and magazine articles. In 1958, Gleason combined forces with disc jockey Jimmy Lyons and the MJQ’s musical director John Lewis to launch the Monterey Jazz Festival, an event which has survived all three of its founders, and remains one of the most successful jazz festivals (both artistically and commercially) in the world. And as the 1960s began, he filmed the first episodes of “Jazz Casual”, a series produced for educational television which captured performances and interviews with John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong and Woody Herman, as well as all of the other musicians mentioned above (save Davis). The photo at above left shows Gleason with Duke Ellington as they taped the pilot episode of “Jazz Casual” (the interview from that show appears in the first book discussed below).

By the dawn of the 1960s, Ralph J. Gleason was recognized as one of the pioneers of jazz criticism. His first reviews appeared in 1934 within the college newspaper at Columbia University, and a few years later, he launched “Jazz Information”, one of the first jazz periodicals in the United States. The Dixieland revival was just starting when Gleason moved to San Francisco. While Gleason preferred modern music, he successfully produced several concerts with the old masters and the young revivalists. In 1950, he joined the staff of the “San Francisco Chronicle” and soon became the first full-time jazz critic on a major newspaper. Within a few years, Gleason was also a regular contributor to “Down Beat”. He developed long-standing friendships with Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Carmen McRae, and the Modern Jazz Quartet, and championed their work through his liner notes, newspaper reviews and magazine articles. In 1958, Gleason combined forces with disc jockey Jimmy Lyons and the MJQ’s musical director John Lewis to launch the Monterey Jazz Festival, an event which has survived all three of its founders, and remains one of the most successful jazz festivals (both artistically and commercially) in the world. And as the 1960s began, he filmed the first episodes of “Jazz Casual”, a series produced for educational television which captured performances and interviews with John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong and Woody Herman, as well as all of the other musicians mentioned above (save Davis). The photo at above left shows Gleason with Duke Ellington as they taped the pilot episode of “Jazz Casual” (the interview from that show appears in the first book discussed below).

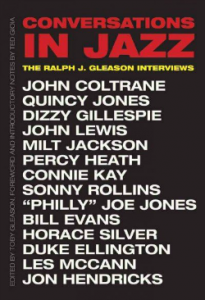

In “Conversations in Jazz”, the first of two new collections of Gleason’s work  edited by his son Toby, and published by Yale University Press, we observe Gleason in 1959-1961, as he interviews some of jazz’s greatest musicians in the comfort of his own living room. There is an easiness about these discussions which transcends the usual musician/journalist encounters. Gleason understood these musicians and could speak to them on their level. In this relaxed atmosphere, Bill Evans could confess that he wasn’t very pleased with his own playing at the time (even though he had just started his legendary trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian!) and Duke Ellington could reveal “If I didn’t know who I was writing for, I wonder what I’d write”. In many cases, Gleason’s timing was quite fortuitous: Sonny Rollins spoke with Gleason just before taking his most famous “sabbatical”—the stories of Rollins practicing on the Williamsburg bridge would soon appear in the New York tabloids; John Coltrane had just started recording for Impulse, and his comments clearly delineate his plans for the “Africa/Brass” album; and Quincy Jones discusses the financial burdens of touring with a big band before his orchestra left for Europe (and nearly bankrupted Jones in the process).

edited by his son Toby, and published by Yale University Press, we observe Gleason in 1959-1961, as he interviews some of jazz’s greatest musicians in the comfort of his own living room. There is an easiness about these discussions which transcends the usual musician/journalist encounters. Gleason understood these musicians and could speak to them on their level. In this relaxed atmosphere, Bill Evans could confess that he wasn’t very pleased with his own playing at the time (even though he had just started his legendary trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian!) and Duke Ellington could reveal “If I didn’t know who I was writing for, I wonder what I’d write”. In many cases, Gleason’s timing was quite fortuitous: Sonny Rollins spoke with Gleason just before taking his most famous “sabbatical”—the stories of Rollins practicing on the Williamsburg bridge would soon appear in the New York tabloids; John Coltrane had just started recording for Impulse, and his comments clearly delineate his plans for the “Africa/Brass” album; and Quincy Jones discusses the financial burdens of touring with a big band before his orchestra left for Europe (and nearly bankrupted Jones in the process).

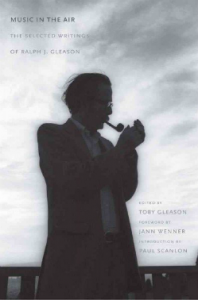

Gleason could have rested on his laurels by the early 1960s, but his career and musical horizons took a surprising turn. While his love for jazz remained strong, he was drawn to the Bay Area’s burgeoning comedy, folk and rock scenes. He was an early fan of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and Jefferson Airplane. In 1967, he helped launch “Rolling Stone” magazine, and to this day—40 years after his death—Gleason’s name still appears on the masthead. Just as he could speak to musicians on their own level, Gleason could speak to teenagers without sounding condescending. His memorial piece for Ben Webster epitomized the saxophonist’s soul for a young generation who was previously unaware of his presence, and his obituary for Janis Joplin captured her essence for the older listeners who had dismissed her work. Many of Gleason’s key pieces for “Rolling Stone” (including the Webster and Joplin pieces) appear in the other new Yale volume, “Music in the Air”. Unlike the material in “Conversations”, all of this material has been published before. Yet having it all in one place allows us a unique opportunity to compare the works. Gleason’s Grammy-winning liner notes to Davis’ “Bitches Brew” seem pretentious and rambling when juxtaposed with the straight-forward essays he wrote for John Handy’s Monterey LP or Simon & Garfunkel’s “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme”. His Olympian survey of jazz history and his extended articles on Ellington and Armstrong hold up well today, although some of the historical details (such as Armstrong’s true birth date) have been corrected in the intervening years. Gleason was quite perceptive about folk music, even as the scene developed around him: he recognized Baez and Dylan as the leaders of the movement and dismissed groups like the Kingston Trio and the Chad Mitchell Trio as commercial knock-offs (he also wrote off Peter, Paul and Mary, which might raise the eyebrows of a few Baby Boomers). And while he clearly appreciated the comedy of Dick Gregory, Jonathan Winters and Bill Cosby, Gleason’s true comedic passion was the work of Lenny Bruce, and an exhaustive 20-plus page essay on Bruce’s career is one of the book’s highlights.

Gleason could have rested on his laurels by the early 1960s, but his career and musical horizons took a surprising turn. While his love for jazz remained strong, he was drawn to the Bay Area’s burgeoning comedy, folk and rock scenes. He was an early fan of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and Jefferson Airplane. In 1967, he helped launch “Rolling Stone” magazine, and to this day—40 years after his death—Gleason’s name still appears on the masthead. Just as he could speak to musicians on their own level, Gleason could speak to teenagers without sounding condescending. His memorial piece for Ben Webster epitomized the saxophonist’s soul for a young generation who was previously unaware of his presence, and his obituary for Janis Joplin captured her essence for the older listeners who had dismissed her work. Many of Gleason’s key pieces for “Rolling Stone” (including the Webster and Joplin pieces) appear in the other new Yale volume, “Music in the Air”. Unlike the material in “Conversations”, all of this material has been published before. Yet having it all in one place allows us a unique opportunity to compare the works. Gleason’s Grammy-winning liner notes to Davis’ “Bitches Brew” seem pretentious and rambling when juxtaposed with the straight-forward essays he wrote for John Handy’s Monterey LP or Simon & Garfunkel’s “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme”. His Olympian survey of jazz history and his extended articles on Ellington and Armstrong hold up well today, although some of the historical details (such as Armstrong’s true birth date) have been corrected in the intervening years. Gleason was quite perceptive about folk music, even as the scene developed around him: he recognized Baez and Dylan as the leaders of the movement and dismissed groups like the Kingston Trio and the Chad Mitchell Trio as commercial knock-offs (he also wrote off Peter, Paul and Mary, which might raise the eyebrows of a few Baby Boomers). And while he clearly appreciated the comedy of Dick Gregory, Jonathan Winters and Bill Cosby, Gleason’s true comedic passion was the work of Lenny Bruce, and an exhaustive 20-plus page essay on Bruce’s career is one of the book’s highlights.

Gleason’s political writing takes up the last portion of “Music in the Air” and it is by far the most prophetic. A life-long progressive, Gleason was frightened by the machinations of Richard Nixon’s presidency, and warned his readers of the dire consequences that could result:

Goebbel’s Big Lie caper was as cool as a freight train and as subtle as a crutch compared to the Catch-22 functioning of the American society. We are not invading Cambodia, Nixon/Agnew said as the troops marched in. In fact, we’re not even there! …The pure purveyors of the new religion—Nixon, Agnew, Reagan, the Sacred Trinity of their hagiography—simply turn it all inside out, twist logic around, deny everything, and go straight ahead doing what they say they are not doing. So-called decent people are in general too decent to make the challenge to them more than a formality.

Sound familiar? This kind of writing landed Gleason on Nixon’s enemies list. Just imagine how Gleason would have reacted to a Donald Trump.

If these books have a single flaw, it is that they expect the reader to come in with a considerable amount of background knowledge. So, if you’re not familiar with the details of the Berkeley student protest movement, Gleason’s reportage will be meaningless. If you don’t know about Coltrane’s “Africa/Brass” album, no editorial comments here will point you to that recording. There are even some references that are a total mystery: in “Conversations”, Gleason asks Quincy Jones, “Do you know Cedric?” Quincy and Ralph know, but we don’t! “Cedric” (we never learn his last name) was apparently a big band arranger at the time. Jones seems interested in hiring him, but there’s no indication that anyone named Cedric ever wrote for Jones’ band. In general, the interviews should have been edited with greater care. There’s a lot of information that has little relevance today (the comparative sales of Dinah Shore singles and jazz albums) and several discussions where the grammar could have been clarified without losing the distinctive voices of the speakers.

Still, these books offer a fine memorial to Ralph J. Gleason. With his open-minded appreciation of the arts, and his clear critical eye, he provided a gateway between the musicians and their audiences. While many fine critics have appeared in the intervening years, how many could claim the same range and credibility as Gleason?