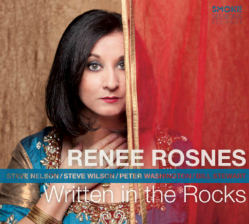

It has been far too long since Renee Rosnes graced us with an album of her music. Her last recordings as a leader were made in 2009, but Rosnes has kept busy performing as a sideperson on albums by Lewis Nash, Brandi Disterheft, Jimmy Greene and Tony Bennett, and composing “The Gallapagos Suite”, a work for jazz quintet which chronicles the history of life on Earth. The seven-movement suite takes the up the majority of “Written in the Rocks” (Smoke Sessions 1601) the first of Rosnes’ albums entirely comprised of her original works. The suite opens with “The KT Boundary” which describes the meteor crash that wiped out the dinosaurs and much of the other species on the planet. After a delicate duet between Rosnes’ piano and Steve Nelson’s vibes, the music surges with an insistent rhythmic motive played under Steve Wilson’s soprano sax. “Gallapagos” has a highly rhythmic and unpredictable drive, intended to portray the surf and wildlife on the islands. Rosnes’ piano rides over the turbulent background of bassist Peter Washington and drummer Bill Stewart, but never loses the subtle touch and shadings that mark her unique style. “So Simple a Beginning” is a waltz denoting the first single-cell amoebas. Wilson (on flute), Rosnes, Nelson and Washington all perform sensitive emotional solos, and near the end, Rosnes adds the perfect splash of color with her delicate improvisations over the final chorus. “Lucy from Afar”, dedicated to the oldest surviving specimen of humans, is also a waltz but the powerful groove is so different from the previous movement that the listener will probably not notice the common meter until the vibes-piano duet midway through the track. The title track features gorgeous interweaving lines between Rosnes and Nelson before Rosnes plays a flowing solo that is overwhelming in its sheer beauty. “Deep in the Blue (Tiktaalik)” describes a primordial creature that was a mix of fish and amphibian, and the deeply swinging walking groove which denotes its movement from sea to land brings out relaxed solos from Wilson, Nelson and Washington. The swiftly moving closing movement “Cambrian Explosion” represents the relatively quick pace of evolution, and is highlighted by an exciting segment of collective improvisation between Rosnes and Wilson. The interplay of the rhythm section is extraordinary throughout this album, and especially noteworthy on the two non-suite pieces which close the album, the medium-swing “From Here to a Star” and the boppish “Goodbye Mumbai” (both of which also include spectacular Rosnes solos). “Written in the Rocks” is a welcome return for Renee Rosnes. Let it mark the beginning of a new series of albums featuring this outstanding musician and composer.

Steve Nelson’s vibes, the music surges with an insistent rhythmic motive played under Steve Wilson’s soprano sax. “Gallapagos” has a highly rhythmic and unpredictable drive, intended to portray the surf and wildlife on the islands. Rosnes’ piano rides over the turbulent background of bassist Peter Washington and drummer Bill Stewart, but never loses the subtle touch and shadings that mark her unique style. “So Simple a Beginning” is a waltz denoting the first single-cell amoebas. Wilson (on flute), Rosnes, Nelson and Washington all perform sensitive emotional solos, and near the end, Rosnes adds the perfect splash of color with her delicate improvisations over the final chorus. “Lucy from Afar”, dedicated to the oldest surviving specimen of humans, is also a waltz but the powerful groove is so different from the previous movement that the listener will probably not notice the common meter until the vibes-piano duet midway through the track. The title track features gorgeous interweaving lines between Rosnes and Nelson before Rosnes plays a flowing solo that is overwhelming in its sheer beauty. “Deep in the Blue (Tiktaalik)” describes a primordial creature that was a mix of fish and amphibian, and the deeply swinging walking groove which denotes its movement from sea to land brings out relaxed solos from Wilson, Nelson and Washington. The swiftly moving closing movement “Cambrian Explosion” represents the relatively quick pace of evolution, and is highlighted by an exciting segment of collective improvisation between Rosnes and Wilson. The interplay of the rhythm section is extraordinary throughout this album, and especially noteworthy on the two non-suite pieces which close the album, the medium-swing “From Here to a Star” and the boppish “Goodbye Mumbai” (both of which also include spectacular Rosnes solos). “Written in the Rocks” is a welcome return for Renee Rosnes. Let it mark the beginning of a new series of albums featuring this outstanding musician and composer.

It’s also been a few years since we’ve heard from tenor saxophonist and flutist Lew Tabackin. Aside from two recordings with the New York Harmonie Ensemble and a John Lewis tribute album led by French guitarist Christian Escoude, Tabackin hasn’t recorded in five years. His self-released trio album, ‘Soundscapes” shows that he is still playing at top form. Tabackin opens the album with a brilliant solo cadenza on tenor before launching into the John Lewis evergreen “Afternoon in Paris”. Tabackin’s solo contrasts diatonic melodic motives with intricately twisting chromatic runs. Working without piano, Tabackin has plenty of freedom harmonically over the flexible backgrounds provided by bassist Boris Kozlov and drummer Mark Taylor. The trio recorded the music live, with all but one track captured at a drum store (Tabackin notes that the sympathetic vibrations from the other drum kits in the shop can be heard in the recording; the effect is probably more noticeable when listening with headphones). Tabackin describes the three originals that follow as “a kind of Japan trilogy”. The atmosphere is set immediately with Tabackin’s evocative flute on “Garden at Life Time” and the stark bass ostinato and delicate cymbals enhance the picture. “B-Flat, Where It’s At” is dedicated to a jazz club in Akasaka, and its not-quite-straight-ahead blues groove provides a welcome contrast to the dramatic improvisations of “Life Time”. The stately waltz “Minoru” memorializes the late saxophone technician Minoru Ishimori, and the bruised tone of Tabackin’s tenor seems to communicate the loss that he felt with the loss of his colleague and friend. “Yesterdays” is one of Tabackin’s favorite flute vehicles, as this is his fifth recording of the Jerome Kern classic. While he uses the same melodic idea to move to long-meter as he had on his version from the 1989 Concord album “Desert Lady”, I admire the new version for the tight interplay between flute and bass on the slow choruses, and for the virtuosic solo of the leader. Billy Strayhorn’s “Day Dream” is taken at a loping tempo which finally locks into a groove after Kozlov and Taylor’s brief move into double-time. Kozlov plays a fine arco solo which turns into a dual improvisation with Tabackin about two-thirds of the way through the track. On the Duke Ellington piece that follows, “Sunset and the Mockingbird”, Tabackin incorporates several Charlie Parker quotes into his flute solos (evidently conjuring up a different Bird than Duke envisioned!). In his notes, Tabackin hopes that Duke purists won’t be offended with his “derangement”; it sounds like Ellington’s music still holds up pretty well. The burning closer, “Three Little Words”, features a remarkable tenor-drums duet at its center, and a delightful ritard at its coda. It’s high time this Jazz Master was recognized by the NEA!

of freedom harmonically over the flexible backgrounds provided by bassist Boris Kozlov and drummer Mark Taylor. The trio recorded the music live, with all but one track captured at a drum store (Tabackin notes that the sympathetic vibrations from the other drum kits in the shop can be heard in the recording; the effect is probably more noticeable when listening with headphones). Tabackin describes the three originals that follow as “a kind of Japan trilogy”. The atmosphere is set immediately with Tabackin’s evocative flute on “Garden at Life Time” and the stark bass ostinato and delicate cymbals enhance the picture. “B-Flat, Where It’s At” is dedicated to a jazz club in Akasaka, and its not-quite-straight-ahead blues groove provides a welcome contrast to the dramatic improvisations of “Life Time”. The stately waltz “Minoru” memorializes the late saxophone technician Minoru Ishimori, and the bruised tone of Tabackin’s tenor seems to communicate the loss that he felt with the loss of his colleague and friend. “Yesterdays” is one of Tabackin’s favorite flute vehicles, as this is his fifth recording of the Jerome Kern classic. While he uses the same melodic idea to move to long-meter as he had on his version from the 1989 Concord album “Desert Lady”, I admire the new version for the tight interplay between flute and bass on the slow choruses, and for the virtuosic solo of the leader. Billy Strayhorn’s “Day Dream” is taken at a loping tempo which finally locks into a groove after Kozlov and Taylor’s brief move into double-time. Kozlov plays a fine arco solo which turns into a dual improvisation with Tabackin about two-thirds of the way through the track. On the Duke Ellington piece that follows, “Sunset and the Mockingbird”, Tabackin incorporates several Charlie Parker quotes into his flute solos (evidently conjuring up a different Bird than Duke envisioned!). In his notes, Tabackin hopes that Duke purists won’t be offended with his “derangement”; it sounds like Ellington’s music still holds up pretty well. The burning closer, “Three Little Words”, features a remarkable tenor-drums duet at its center, and a delightful ritard at its coda. It’s high time this Jazz Master was recognized by the NEA!

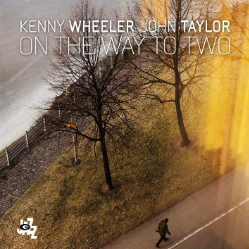

My heart sank when I received “On the Way to Two” (CamJazz 5054). This collection of 2005 duets had been issued as a memorial to flugelhornist Kenny Wheeler, but by the time the album was released, Wheeler’s duet partner, pianist John Taylor had also passed away. Wheeler and Taylor were frequent collaborators, having comprised two-thirds of the group Azimuth (vocalist Norma Winstone is now the only survivor of that revolutionary ensemble ) and on these previously unissued recordings, they instinctively find ways to compliment each other’s lines. Wheeler’s sound was an intriguing mix of bright articulation and wounded tone, and even while staying within the harmonic structure, he incorporated pitch bending and other avant-garde techniques as expressive devices. Taylor could be equally adventurous, with his sparkling tone balancing his sophisticated use of rubato rhythm and advanced harmonies. The album displays just how well they suited one another: Taylor’s robust energy and sunny voicings took the edge off Wheeler’s melancholy sound and brightened the moody feeling of the trumpeter’s compositions. On the three improvised pieces (all named “Sketch” and situated at pivotal moments in the album), the two men revel in exploring each other’s ideas, ranging from melodic and harmonic motives to using the piano in unconventional ways (strumming the strings or striking the frame; and in the case of “Sketch No. 3” using an intriguing combination of both techniques). The album’s closer may be the most heart-wrenching version of Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower is a Lovesome Thing” ever recorded. Taken at a funereal tempo, it gives Wheeler and Taylor the opportunity to examine every note for its deepest meaning. Wheeler makes a powerful lunge into the lowest register of his horn near the end of the first chorus, and when the trumpeter moves into his solo, Taylor shows great restraint by letting the improvised melodies guide the rhythmic flow. When Taylor takes over for his own solo, his lines contain a remarkable emotional power, and for a while, he develops the motives as if he were a classical composer. The final juxtaposition of Wheeler’s tortured melody statement with Taylor’s fluttering arpeggios creates an emotionally overwhelming close to this remarkable album. Whether or not you believe that Wheeler and Taylor are together again somewhere in the hereafter, we can all be grateful that they created heavenly music while they were here on Earth.

) and on these previously unissued recordings, they instinctively find ways to compliment each other’s lines. Wheeler’s sound was an intriguing mix of bright articulation and wounded tone, and even while staying within the harmonic structure, he incorporated pitch bending and other avant-garde techniques as expressive devices. Taylor could be equally adventurous, with his sparkling tone balancing his sophisticated use of rubato rhythm and advanced harmonies. The album displays just how well they suited one another: Taylor’s robust energy and sunny voicings took the edge off Wheeler’s melancholy sound and brightened the moody feeling of the trumpeter’s compositions. On the three improvised pieces (all named “Sketch” and situated at pivotal moments in the album), the two men revel in exploring each other’s ideas, ranging from melodic and harmonic motives to using the piano in unconventional ways (strumming the strings or striking the frame; and in the case of “Sketch No. 3” using an intriguing combination of both techniques). The album’s closer may be the most heart-wrenching version of Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower is a Lovesome Thing” ever recorded. Taken at a funereal tempo, it gives Wheeler and Taylor the opportunity to examine every note for its deepest meaning. Wheeler makes a powerful lunge into the lowest register of his horn near the end of the first chorus, and when the trumpeter moves into his solo, Taylor shows great restraint by letting the improvised melodies guide the rhythmic flow. When Taylor takes over for his own solo, his lines contain a remarkable emotional power, and for a while, he develops the motives as if he were a classical composer. The final juxtaposition of Wheeler’s tortured melody statement with Taylor’s fluttering arpeggios creates an emotionally overwhelming close to this remarkable album. Whether or not you believe that Wheeler and Taylor are together again somewhere in the hereafter, we can all be grateful that they created heavenly music while they were here on Earth.