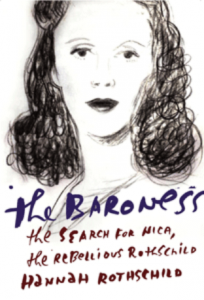

The Baroness Pannonica Rothschild de Koenigswarter was one of a handful of non-musicians who played small but pivotal roles in the development of jazz. Nica, as she was known, was a habitué of New York’s jazz clubs from the late 1940s until her death in 1988. But more than being just a supporter of the music, she was a supporter of musicians, using her wealth and status to assist those who needed help paying the rent, buying groceries or rescuing their horn from a local pawnshop. She was, after all, a member of the Rothschild family, and the family had both abundant funds and a dedication to helping the less fortunate. For the past several years, Nica’s great-niece Hannah Rothschild has researched the Baroness’ life, creating radio and television documentaries for the BBC and now a book “The Baroness” (Knopf). The video documentary has played at film festivals and cable TV here in the US, and is available here as a PAL format DVD. Many of the interviews in the book come from the video, but Rothschild uses the book to expand upon Nica’s story. Indeed, the reader looking for information about Nica’s support of jazz and its musicians must go to the halfway point of the book to find that part of the tale.

The Baroness Pannonica Rothschild de Koenigswarter was one of a handful of non-musicians who played small but pivotal roles in the development of jazz. Nica, as she was known, was a habitué of New York’s jazz clubs from the late 1940s until her death in 1988. But more than being just a supporter of the music, she was a supporter of musicians, using her wealth and status to assist those who needed help paying the rent, buying groceries or rescuing their horn from a local pawnshop. She was, after all, a member of the Rothschild family, and the family had both abundant funds and a dedication to helping the less fortunate. For the past several years, Nica’s great-niece Hannah Rothschild has researched the Baroness’ life, creating radio and television documentaries for the BBC and now a book “The Baroness” (Knopf). The video documentary has played at film festivals and cable TV here in the US, and is available here as a PAL format DVD. Many of the interviews in the book come from the video, but Rothschild uses the book to expand upon Nica’s story. Indeed, the reader looking for information about Nica’s support of jazz and its musicians must go to the halfway point of the book to find that part of the tale.

However, what precedes Nica’s jazz life is nearly as fascinating. Rothschild delves back into her early family history to explain the development and growth of the Rothschild banking empire. From the beginning, the Rothschild women were not allowed to be part of the family business, and the family took little interest in seeing that its female members were properly educated or prepared for their adult lives. In scenes that would make the heads of modern child psychologists spin, Rothschild describes Nica’s sheltered and restrictive lifestyle. The Rothschild girls were raised in a country home by a team of nurses, fed an exquisitely cooked but monotonous breakfast menu alternating eggs and fish, and forced to wear the same lace dresses every day with only a different colored ribbon for each girl. They were educated by governesses in little more than piano and sewing, with no attention given to the biological changes they would face in puberty. They had few playmates and were not allowed to run free in the family’s massive estate. They did not see their parents often, and were only allowed to join the family for nightly dinner after their sixteenth birthday.

Nica became a rebel when she left the family nursery at sixteen. Through her father and brother, she had developed a passion for jazz, and now that she could stay up past 9:00, she hosted record listening parties at the mansion from 2 to 5 in the morning. As a debutante, she dated musicians and bandleaders, but eventually married Baron Jules de Koenigswarter, who shared Nica’s love for flying, but not her love for jazz. The couple had a house near Normandy, France when World War II broke out and while Jules enlisted in the Free French Army right away, Nica and her newborn children remained at the house until days before the Nazis marched in. Nica moved her children to the US, and then enlisted with the Free French Army while back in London. Going against direct orders, she smuggled herself to Africa where she miraculously found her husband’s division and worked with them as a driver and decoder. Jules’ strict manner and attention to details served him well during the war, but it caused troubles with Nica when the war was over. Jules became a diplomat, and Nica had little interest for her new spousal duties. In the late 1940s, she traveled to New York as an escape from her husband and their five children. As she was on her way to the airport to come home, she stopped at Teddy Wilson’s apartment, and the pianist played her Thelonious Monk’s then-new recording of “Round Midnight”. By Nica’s own admission, the music changed her life, and she decided to abandon her marriage, move to New York and pursue her love of jazz.

Rothschild’s extensive research (despite a lack of cooperation from members of her family) offers a vivid look at Nica’s early years, and her work is equally impressive as she fills in details about Nica’s jazz life in New York. She reveals that Nica and Monk did not meet until his 1954 concert in Paris, and that they were introduced to each other by mutual friend Mary Lou Williams. She also details Nica’s attempts to bring Monk to the London stage, only to be foiled by then-current musician union rules. The familiar story of Charlie Parker’s death in her apartment is recounted here, but Rothschild offers startling information about the doctor who treated Parker in his final days. Nica was evicted from the Stanhope Hotel after Parker’s death, and Rothschild tells how Nica picked her new residence at the Bolivar Hotel so that she could provide a rehearsal, composing and jamming space for Monk. She became Monk’s personal manager and was part of his creative team starting with his album “Brilliant Corners” and when Monk regained his cabaret card, she helped him land a long-term engagement at the Five Spot (including buying a new piano for the club).

The most harrowing part of Rothschild’s narrative comes with her account of a racially motivated drug bust in Delaware. Nica was driving Monk and Charlie Rouse to a gig in Baltimore when Monk announced that he needed to use the restroom. Nica pulled into a small motel, Monk went straight to the facilities, and then asked the clerk for a glass of water. The clerk was frightened of Monk’s huge size and unintelligible speech, and called the state troopers. The police beat Monk to unconsciousness, and arrested both Nica and Rouse. When searching Nica’s Bentley, they found $10 worth of marijuana in the trunk. Nica took the rap to save Monk, but Monk still lost his cabaret card, and Nica was sentenced to a large fine, three years in prison and instant deportation upon release. Thankfully, Nica was set free on a technicality. Rothschild’s account offers excerpts from the court transcripts and a heart-rending letter from Nica to Mary Lou Williams written on the evening before her appeal. The depth of mid-1950s prejudice has rarely been recounted with such striking detail.

Hannah Rothschild only met Nica a few times in person, and she claims not to have more than a rudimentary knowledge of jazz. However, her skills as a researcher and documentarian have led her to find the right people to interview and to sort out the facts surrounding her mysterious great-aunt. At times, she openly questions whether Nica deserved all the fame she received. But her work shows that Nica had a positive effect on the musicians she loved. Nica didn’t look for tributes in her own life, but they came in songs written and dedicated to her by great musicians. Now, at least one member of her family has offered a different, but equally heartfelt tribute. “The Baroness” offers an unique look at this flawed but noble lady.